Exploring MVU and Functional Paradigms in Xamarin.Forms

This week saw one of Microsoft’s biggest conferences transition to a completely online format. We won’t discuss the fact that this year’s conference was supposed to be held just 30 minutes from my house and that I was hoping to attend, but I do want to talk a bit about some of this year’s announcements in the .NET space that have taken over my brain. There’s plenty to be excited about - new Azure services, production-ready (?) Blazor, .NET Core 4 - err… I mean .NET 5 - but what has really monopolized my thinking is how functional concepts keep making their way into C#.

I found this in two distinct efforts that were mentioned at this year’s Build. The more obvious of the two is the addition of Records and Init-only Properties in C# 9.0. This, along with some nice improvments to pattern matching, will mean that C# devs will be able to reap some more of the performance and readability benefits of a more Functional approach. The second place, was with the introduction of a technology that is still a year out from its first GA version: .NET MAUI (Multi-platform App UI). The idea here is to finally unify the split Xamarin/UWP experiences into a single developer experience. Now, this on its own is really cool (IOS, ANDROID, AND WINDOWS ALL IN THE SAME PROJECT?!?! GASP), but they snuck something in here that again appears to point towards Functional paradigms coming enmasse to C#-land, namely, first class support for MVU (Model-View-Update).

Now C# devs are really familiar with M’s and V’s - we’re all about MVC and MVVM - but I don’t think very many of us are familiar with MVU. I’ve heard it discussed by people who have their toes in the Functional world, but never really dug in. In fact, I’ve always wanted to be one of those people that has their toes in the Functional world, but I’ve always given up long before I understood anything in a real sense. So I’ve convinced myself to give it another try, but this time in the hopes that I might get some insight into the future of mobile development on the .NET platform.

So that’s the plan (and the purpose of this article - only took me 3 paragraphs to get to it). I’m going to use F# and Xamarin.Forms to try out MVU in the hopes that I might gain some insight into what MAUI may bring.

This may be a completely foolish attempt, but I think it has the highest possibility of getting me to actually try my hand at F#. Worst case, you’ll never see this, because I’ll never post it. Its a perfect system.

Fabulous F# and Xamarin.Forms

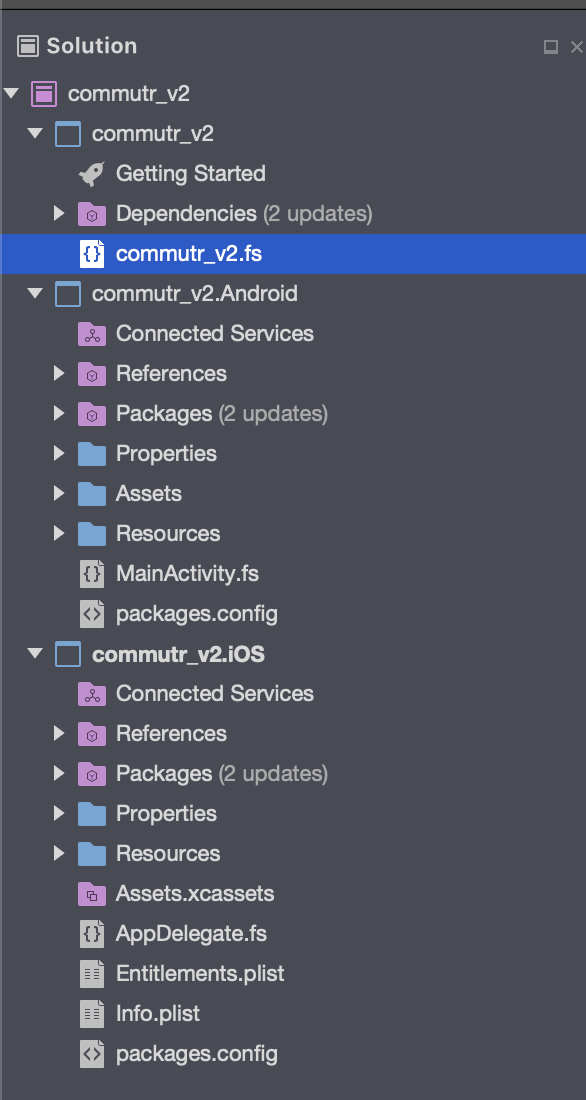

Anyway, I started by doing some googling for MVU frameworks meant to work with Xamarin.Forms and within seconds I had run into Fabulous for Xamarin.Forms. It looked like everything I needed, including a template project - which was a real plus. I won’t bore you with the setup, just know that it was minimal (a couple of dotnet CLI commands) and that it resulted in this:

Thats right folks, three F# projects, no XAML, and no C#.

Side Note: Project Name

You may be questioning why this project name is not “MvuDemo” or “HelleWorldMvu” or something. My plan is to ultimately recreate an app that I wrote a few years ago, which I use for mileage and fuel economy tracking. While its not important to this particular post, I figured I’d let you all in on this little personality tick of mine. When I start a project of any kind, I start with an end goal so large its impossible.

There’s a good chance commutrv2 will never actually happen. When I first started this post, I assumed I would be able to get well beyond explaining the demo app. I quickly realized I needed to break down the demo app just so that I could understand it. So there you have it. When it comes to personal goals, I always over promise and under deliver.

Was that a waste of your time? I hope not … now where were we?

Oh right, here’s the contents of the single F# file generated in the shared project:

// Copyright 2018-2019 Fabulous contributors. See LICENSE.md for license.

namespace commutr_v2

open System.Diagnostics

open Fabulous

open Fabulous.XamarinForms

open Fabulous.XamarinForms.LiveUpdate

open Xamarin.Forms

module App =

type Model =

{ Count : int

Step : int

TimerOn: bool }

type Msg =

| Increment

| Decrement

| Reset

| SetStep of int

| TimerToggled of bool

| TimedTick

let initModel = { Count = 0; Step = 1; TimerOn=false }

let init () = initModel, Cmd.none

let timerCmd =

async { do! Async.Sleep 200

return TimedTick }

|> Cmd.ofAsyncMsg

let update msg model =

match msg with

| Increment -> { model with Count = model.Count + model.Step }, Cmd.none

| Decrement -> { model with Count = model.Count - model.Step }, Cmd.none

| Reset -> init ()

| SetStep n -> { model with Step = n }, Cmd.none

| TimerToggled on -> { model with TimerOn = on }, (if on then timerCmd else Cmd.none)

| TimedTick ->

if model.TimerOn then

{ model with Count = model.Count + model.Step }, timerCmd

else

model, Cmd.none

let view (model: Model) dispatch =

View.ContentPage(

content = View.StackLayout(padding = Thickness 20.0, verticalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center,

children = [

View.Label(text = sprintf "%d" model.Count, horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center, width=200.0, horizontalTextAlignment=TextAlignment.Center)

View.Button(text = "Increment", command = (fun () -> dispatch Increment), horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center)

View.Button(text = "Decrement", command = (fun () -> dispatch Decrement), horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center)

View.Label(text = "Timer", horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center)

View.Switch(isToggled = model.TimerOn, toggled = (fun on -> dispatch (TimerToggled on.Value)), horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center)

View.Slider(minimumMaximum = (0.0, 10.0), value = double model.Step, valueChanged = (fun args -> dispatch (SetStep (int (args.NewValue + 0.5)))), horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.FillAndExpand)

View.Label(text = sprintf "Step size: %d" model.Step, horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center)

View.Button(text = "Reset", horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center, command = (fun () -> dispatch Reset), commandCanExecute = (model <> initModel))

]))

// Note, this declaration is needed if you enable LiveUpdate

let program = XamarinFormsProgram.mkProgram init update view

type App () as app =

inherit Application ()

let runner =

App.program

#if DEBUG

|> Program.withConsoleTrace

#endif

|> XamarinFormsProgram.run app

#if DEBUG

// Uncomment this line to enable live update in debug mode.

// See https://fsprojects.github.io/Fabulous/Fabulous.XamarinForms/tools.html#live-update for further instructions.

//

do runner.EnableLiveUpdate()

#endif

// Uncomment this code to save the application state to app.Properties using Newtonsoft.Json

// See https://fsprojects.github.io/Fabulous/Fabulous.XamarinForms/models.html#saving-application-state for further instructions.

#if APPSAVE

let modelId = "model"

override __.OnSleep() =

let json = Newtonsoft.Json.JsonConvert.SerializeObject(runner.CurrentModel)

Console.WriteLine("OnSleep: saving model into app.Properties, json = {0}", json)

app.Properties.[modelId] <- json

override __.OnResume() =

Console.WriteLine "OnResume: checking for model in app.Properties"

try

match app.Properties.TryGetValue modelId with

| true, (:? string as json) ->

Console.WriteLine("OnResume: restoring model from app.Properties, json = {0}", json)

let model = Newtonsoft.Json.JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<App.Model>(json)

Console.WriteLine("OnResume: restoring model from app.Properties, model = {0}", (sprintf "%0A" model))

runner.SetCurrentModel (model, Cmd.none)

| _ -> ()

with ex ->

App.program.onError("Error while restoring model found in app.Properties", ex)

override this.OnStart() =

Console.WriteLine "OnStart: using same logic as OnResume()"

this.OnResume()

#endif

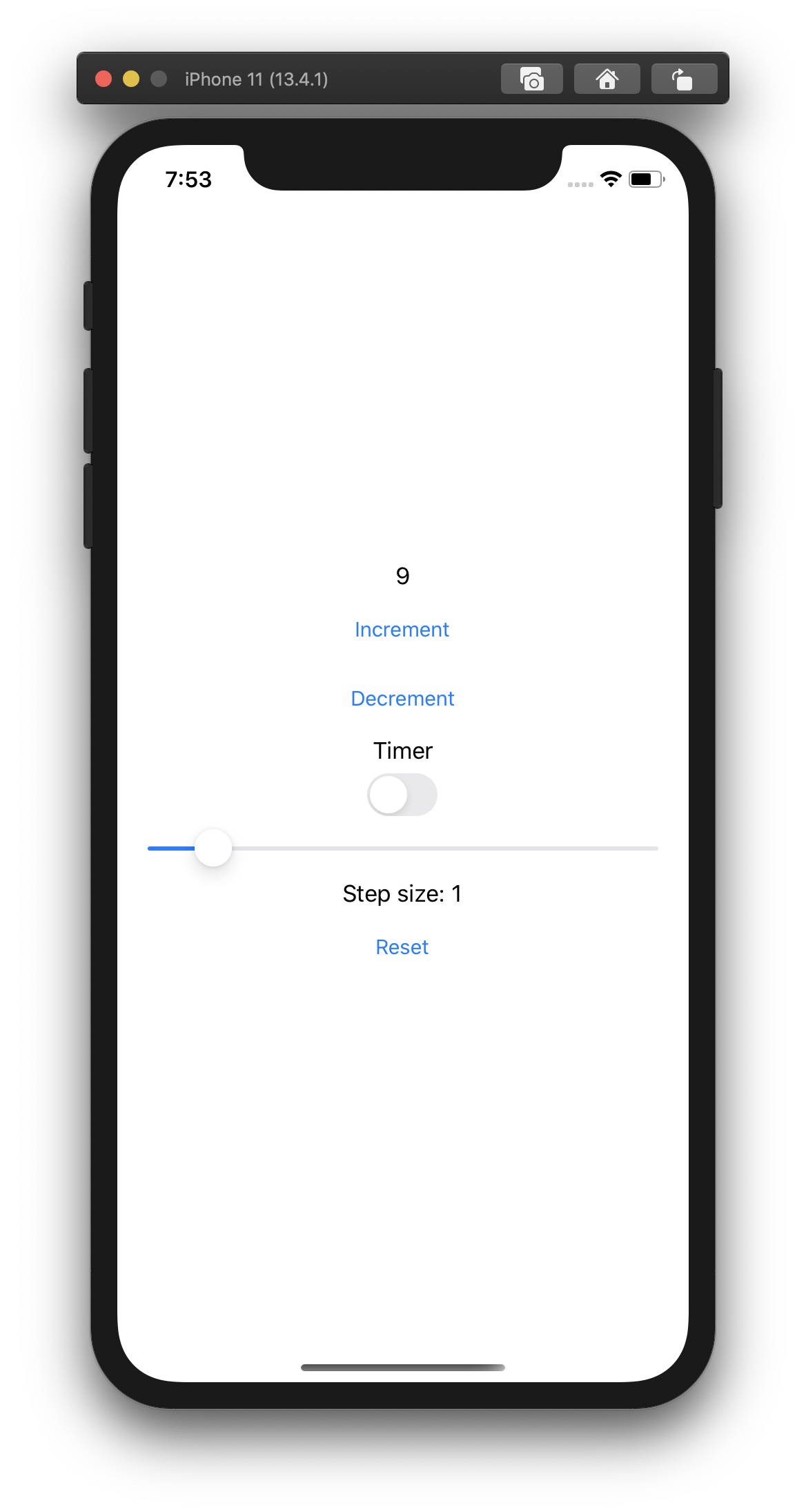

This is a pretty complicated example to start with, and it took me a little bit by surprise. But the gist of this example is that it is a counter, with a slider to adjust the “step” of the increment, and an optional timer feature which increments the count by the step amount every 200ms. Here’s the UI to help you picture it.

Side Note: Acknowledging My Own Limits

Just as a note, we’re going to skip everything from

let program = XamarinFormsProgram.mkProgram init update viewdown as this is really just kind of “wiring” that sets up the framework. I included it here as it is part of the file and might be interesting for those who are a little more advanced in their knowledge of F# Xamarin development, but - to be truthfully honest - I don’t understand most of it.

Breaking It Down

Now I know there’s a lot of code here and on top of that, there’s quite a bit of syntax that looks quite strange if you’re not familiar with F#, but there’s really three key portions of this app that I think break down quite nicely. I know what you’re thinking, “Three you say? You mean the same as the number of letters in the acronym?” And you’re right, but you don’t have to be so smug about it.

First: The Model (and the Initialization Thereof)

type Model =

{ Count : int

Step : int

TimerOn: bool }

type Msg =

| Increment

| Decrement

| Reset

| SetStep of int

| TimerToggled of bool

| TimedTick

let initModel = { Count = 0; Step = 1; TimerOn=false }

let init () = initModel, Cmd.none

In the above, we have two types. One is a record representing the data that will drive the app, and we’ve decided to call it Model (because its… the model). But the second one is actually what we call a Discriminated Union. The best description I’ve heard so far of Discriminated Unions is that they’re “enums on steroids”. They are similar to an enum where each value can be an “object” and they’re really powerful. Anyway, all that syntax aside, this Discriminated Union is what we call the message. The importance of the message is that it tells us how the model should change. For those familiar with tools like ReactRedux, the message is similar to your action.

Next we have two let statements. The first describes the initial state. Notice that we do not specify that it is of the Model type, because types are inferred in F#. Its magic and its a lot less typing, and I’m not sure if I love it or hate it. The second let statement is essential, it is a function that returns the intial state (which we created in the previous statement) and a command. Commands are another key concept in MVU.

As I understand it, the key reason for having commands is that they allow us to fire messages from within the update function (which we will discuss in more detail later). But there are several different kinds of commands which can be used to fire messages in different kinds of ways.The one you’ll see used in this example is Cmd.ofAsyncMsg. TThis command allow asynchrous messages to be piped in to our update function, which allows us to complete asynchronous tasks like waiting on a timer, making a database call, or issuing and resolving a REST request. I’m skipping ahead a bit here, but this should make more sense in a minute.

So there we have it, the model, the message, and our initalizer.

Next Up: Our Update Function

let timerCmd =

async { do! Async.Sleep 200

return TimedTick }

|> Cmd.ofAsyncMsg

let update msg model =

match msg with

| Increment -> { model with Count = model.Count + model.Step }, Cmd.none

| Decrement -> { model with Count = model.Count - model.Step }, Cmd.none

| Reset -> init ()

| SetStep n -> { model with Step = n }, Cmd.none

| TimerToggled on -> { model with TimerOn = on }, (if on then timerCmd else Cmd.none)

| TimedTick ->

if model.TimerOn then

{ model with Count = model.Count + model.Step }, timerCmd

else

model, Cmd.none

So in the above, we only have two statements. timerCmd is an asynchronous function which waits 200ms before returning a TimedTick, which you may recall was one of the cases in our Discriminated Union. This is then piped into an async message command, which will issue the TimedTick message when it is returned by our async call. The |> (forward pipe) syntax is another thing that feels really strange, but it allows you to chain together functions quickly and with minimal fuss.

Next you’ll find the real substance of our apps logic, the update function. update take in two parameters msg and model. Simply put, model tells us the current state of the app and msg tells us what action we should perform on that state. By pattern matching on msg we can call different functions based on the message we received. Note that the function should have the same return as our init function from earlier: the updated model, and a command to call (if any).

I think most of these are self explanatory (assuming you understand the with syntax, which creates a copy of the object with whatever changes are specificed): Increment returns the current model with count increased by the current Step amount, decement does the opposite, etc. But the last two cases are where you can see everything come together.

In the case where msg is TimerToggled, we return the model with an update to the TimerOn field with the value that we were supplied. As for the command, we return timerCmd if the value of TimerOn is true and no command if not.

The last case - where msg is TimedTick - is the message sent when timerCmd has completed. If the timer is on, we want to update the count by step and call timerCmd again. This puts us in a loop where the timerCmd is called, count is updated and then its called again. We can break this loop, by sending the TimerToggled message with a value of false.

So that’s the update function. At its core, its a reducer that applies changes to the state based on the message that is sent. Again if you’re familiar with ReactRedux, you’ve seen this before.

Finally: The View

let view (model: Model) dispatch =

View.ContentPage(

content = View.StackLayout(padding = Thickness 20.0, verticalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center,

children = [

View.Label(text = sprintf "%d" model.Count, horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center, width=200.0, horizontalTextAlignment=TextAlignment.Center)

View.Button(text = "Increment", command = (fun () -> dispatch Increment), horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center)

View.Button(text = "Decrement", command = (fun () -> dispatch Decrement), horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center)

View.Label(text = "Timer", horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center)

View.Switch(isToggled = model.TimerOn, toggled = (fun on -> dispatch (TimerToggled on.Value)), horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center)

View.Slider(minimumMaximum = (0.0, 10.0), value = double model.Step, valueChanged = (fun args -> dispatch (SetStep (int (args.NewValue + 0.5)))), horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.FillAndExpand)

View.Label(text = sprintf "Step size: %d" model.Step, horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center)

View.Button(text = "Reset", horizontalOptions = LayoutOptions.Center, command = (fun () -> dispatch Reset), commandCanExecute = (model <> initModel))

]))

The view function returns the UI based on the current state. The view function should always be pure, meaning that it should contain no side effects and should always return the same output with the same input. In this example, we’re using the standard Xamarin.Forms UI elements to render a Content Page with a Stack Layout. The children of the stack layout, are a Label for the count, a Button for increment and decrement, etc.

Notice that view takes two arguments, model and dispatch. As with everywhere else, model is the current state of our app. The second argument, dispatch is a special function that allows us to send messages to our update function.

There are a few places where dispatch is used. The “Increment” button dispatches an Increment message, on each click. The “Timer” switch, displays the current state of model.TimerOn and dispatches the TimerToggled message with the updated value when it is toggled. The slider calls SetStep based on the value of slider as it changes.

In each case, the UI element displays the current state of the Model (where necessary) and uses dispatch to send messages to update. This is the magic of MVU. Data flows in a very linear fashion, as the current state is passed to the view and the view dispatches an update. Rinse, repeat. (So I guess its more of a circular flow?)

Final Thoughts

There are plenty of things I don’t like about F#. For one, I think that its easy for a language that encourages less code to encourage less readability. At the same time, I recognize that more verbose does not necessarily equal more readable, so… to each their own. What I really like about this approach is the same thing I have come to love about functional components in React (which is the only other “functional” environment that I regularly interact with). Because the view can only read the current state and dispatch updates to the state, its very easy to reason about what happens in any given scenario.

That’s what excites me about MAUI. If the result is MVU’s ability to make code more “reasonable” with the familiarity of C#, I really think I could be sold on it. The beauty of all this is that there are no plans to get rid of XAML or MVVM, so I’ll always have that to fall back on, but I think there is really something to be said for the simplicity of MVU. That being said, this is just me scratching the surface. In order to do a full scale app (like Commutr V2), I’ll have to figure out how to leverage composition to create smaller, more manageable components that can be combined together to accomplish complicated tasks.

But that’s for a another day. ‘Til next time!

(If I ever get around to it…)

Turns out I did get around to it. Go check out Exploring MVU Part 2: Composition.